Sunday, April 29, 2012

Saturday, April 28, 2012

New Season's Apples

Tonight, miles away, I can hear the start of every speedway race, a revving pitch of juiced up V8s across the flatlands of the old swamp country. An imminent thunderstorm is trying hard to make contact. We are all waiting for it. In between races, the storm lets out a low rumble. New westerlies work on changing the big trees' minds. The frogs are in romance mode - I think I ran over one who launched bravely onto the tarmac after his mate. Sand Patch swells in the coasthills. The toilet flushes next door.

People are burning off because the authorities have just started giving out permits after a scary, tinderbox summer. Cycling through the night's quiet, dark roads, I can smell the different kinds of wood smoke (swamp, mallee, eucalypt, balga, taylorina). I can smell the drains filled with last night's downpour, new flowers, turned earth, damp peppermint leaves, steaming afternoon sun-warmed bitumen.

Along the highway into town, the casuarinas are flowering. It's a drive-by flash of brown and green according to their sex. Sheoake. Heoke. Sheoake. Heoake ... A local supermarket boasts new season apples. Smoke lays across the glass-off.

It's been warm and grey and nobody knows what to wear. We sweat in a filtered sun and freeze in the shade. We put on our sunglasses and then take them off again. Beanies are still bothersome. The quickening of the sun over the horizon at the end of the day has taken us by surprise. All of a sudden I have to turn my car's headlights on before the close of business.

People are burning off because the authorities have just started giving out permits after a scary, tinderbox summer. Cycling through the night's quiet, dark roads, I can smell the different kinds of wood smoke (swamp, mallee, eucalypt, balga, taylorina). I can smell the drains filled with last night's downpour, new flowers, turned earth, damp peppermint leaves, steaming afternoon sun-warmed bitumen.

Along the highway into town, the casuarinas are flowering. It's a drive-by flash of brown and green according to their sex. Sheoake. Heoke. Sheoake. Heoake ... A local supermarket boasts new season apples. Smoke lays across the glass-off.

It's been warm and grey and nobody knows what to wear. We sweat in a filtered sun and freeze in the shade. We put on our sunglasses and then take them off again. Beanies are still bothersome. The quickening of the sun over the horizon at the end of the day has taken us by surprise. All of a sudden I have to turn my car's headlights on before the close of business.

Thursday, April 26, 2012

Dark Work

He

looked at her when he was straight. He’d look right at her, something else

running through his mind. Just stared with water eyes straight at her.

You’re

the quick one. You are clever. A herring queen, you are. Not like that dozy

wench.

Dozy

wench, said Weed.

Go

on. Hold the wood for me, Weed. Don’t be afraid. Hold it like this.

He

placed her hands with his red, freckled fingers so her thumbs reached the centre of the log.

She

held the piece of wood and he swung the axe. She moved both thumbs and watched the

axe bite into where they had lain a moment before. The log cleaved in two, spilling

with startled ants.

You

a brave girl, Weed. Brave. He nodded approval at her and stumped up the hill, swinging

his axe and whistling.

Old Salt and I spent delightful morning yesterday cruising around Limestone Head, trolling for salmon and bonito. At Bald Head, the autumn glass-off ceased. It's always a game changer, Bald Head. The ocean turned a deep, gunbarrel grey. The boat started reacting against a new swell that slammed into the headland, creating a chaotic backwash. Suddenly I couldn't find my feet. I looked to where the Southern Ocean is only briefly quelled by Eclipse Island. Birds worked schools of sardines, which meant bigger fish beneath but I really didn't want to head around there.

In the afternoon I went back to the thesis and in particular, the scenes on Eclipse Island where the sealer Samuel Bayley took a young Menang woman and another of his Aboriginal abductees, little Weed, in 1826. They were alone on the island for weeks with Bayley, before Lockyer acted on William Hook's testimony and sent his man out there to rescue them. No one, no one, knows anymore what happened out at Eclipse, except that the Menang woman returned to King George Sound in a shocking physical and emotional state. Weed was put on the Amity with her abductor and sent to Sydney.

I've been avoiding writing this chapter. There are only so many reasons why a grown man would abduct two girls, one an adolescent and the other seven years old, and imprison them an island. I wrote some nasty stuff today and I'm feeling a bit fucked up tonight. In the last few months I've researched Stockholm Syndrome and literary renditions of pedophilia and infanticide for the non fiction section of my thesis. It sounds weird but writing fiction about these things is much harder and more personal. Sometimes I wonder how writers, male or female, cope with what they are channelling (because writing fiction, when it's really cranking, is definitely channelling, and I think that is the rub). Margaret Attwood depicts beautifully the bruised but pragmatic sensibilities of abused sex workers in both Oryx and Crake and The Year of the Flood. She also took the unusual step of auctioning off character's names for Flood, to fund international victims of torture.

On 1820s Bass Strait, G.A. Robinson met sealers who took girls to live with them. Monroe, the self-proclaimed policeman of the Straits, 'cohabited' with a Pallawah girl since she was an infant. It's difficult to tell past Robinson's anti-sealer rhetoric as to whether some of the Straitsmen were honouring a traditional Aboriginal sensibility where they assumed maintenance of a potential bride for a decade or so before they were actually married, or whether the men were just outright pedophiles who wanted workers and concubines but didn't want to deal with offspring. One academic colleague in Launceston stays vehemently with the latter.

On a lighter note (phrew!), today I took an internet psychopath test and realised that I'm definitely not one, though in a moment of spectacularly poor judgement, I probably nearly married one once. I have decided to portray Bayley as possessing the qualities of what these days would described as psychopathic. Manipulative, insensible to ethics, punishment or the feelings of others. In other words, he never signed the unspoken social contract that the rest of us unwittingly adhere to for our own safety. My layman's diagnosis of this character has helped me into and beyond whatever happened on Eclipse Island during those weeks.

For the moment.

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

Tuesday, April 24, 2012

As Good As It Gets

This is where I go to work every day. It is the building that houses the satellite country campus of a major West Australian university. 'Down here', we wave to the city to notice us occasionally and the rest of the time we happily revel in the beautiful space provided us and hope the city won't cotton on to how good we've got it.

It used to be the customs building, back when the sea walked up to the verandas and all the nation's highways were sea borne. You could liken it to contemporary interstate fruit inspection points on the Nullabor, when the contents of your vessel gets spilled out on the road for scrutiny.

Nowadays, students spill out of the front doors after a tutorial, still buzzing with discussions from their weekly readings. I did my whole degree in this building, apart from a sojourn to Otago in New Zealand. Even though I now work externally from a different university, I managed to hold on to my post grad's desk and 'being in the loop' has proved a life line in my task as a regional PhD student.

Lucky, huh? Sometimes, even when life gets in the way, I have to pinch myself.

Saturday, April 21, 2012

Whale Grave

That

day, on the other side of the hill, we found four huge skulls. Brown with oil,

the skulls lay in a neat row, identical in size; they were from the last great

whale stranding. Behind them rose the burial mounds, fallen in where the

innards had rotted, rib bones of the leviathans looking like strange plants

poking out of the earth.

This

place is where their carcasses end up. This is where the whales go when they

have died in front of humans. They are towed to a boat ramp and craned onto a

flatbed truck. There is no brine to smooth and support their perfect bodies.

Sand sticks to their skin. People take photographs of the ungainly mess with

mobile phones and then the whales are driven away from the sea forever.

From Whale, Daughter, by Sarah Toa.

Overland, issue 205, 2011.

Wednesday, April 18, 2012

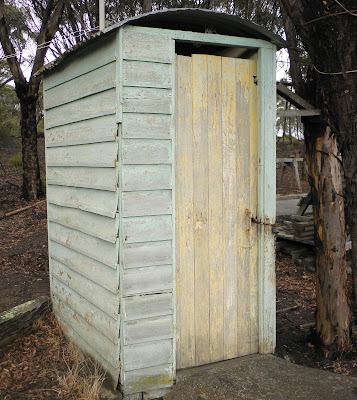

Shack

Dynamite boxes all the way from Texas ... the local tip has a good supply of these garden planters thanks to the mining companies. The boxes are stamped with warnings about the carcinogenic qualities of dynamite. I saw them only after I'd carted them back to Kundip. Ah, dynamite, shmynomite.

A tank stand of Kundip stone and abalone shells.

I'm a bit proud of this tank stand. It stashes every empty wine bottle from the ghost town of Kundip's most splendid New Years' Eve. I built it the next day, sweating most of NYE2012's wine back out.

Plus, when I went there last week, the tank was FULL and still upright.

So I had to connect up an overflow tank to get another 1,000 litres. Ever tried to connect plumbing with imperial and metric pipes, using material garnered from the tip? The process involves deep groans when the sun damaged 1960's pipe breaks in half as you are hack sawing through salvaged 1990's poly to fit into a twenty first century tank. You reckon that angle on the overflow looks funny? Hey, I'm no Clancy but she works.

Digger agrees.

Building stuff on my own when I have no experience and no other brain to run things by is pretty daunting. I've found that about 30 percent of what I build needs to get dismantled. A design FAIL can be quite crushing on a hot day when I've got to cook my own dinner.

The shack began with good, straight foundations. As I head outwards, the shack gets curlier and wobblier. She's becoming a wibbly, wobbly shack, the further out I go, emulating the curly qualities of all copper ghost towns ...

Sunday, April 15, 2012

Musical Occupations

The evening planes from Perth to Melbourne fly over Kundip skies ...

As I drove in on Easter Sunday, Yunupingu sang on the car stereo. The country is exciting around here. It changes every few hundred metres, round a corner or crest a hill and the scrubby melalucas and red stone morph into salmon gums and quartz. In the morning, I followed the zoologist on a trek down Road Eleven, past the Barrens and into casuarina country, to visit his beautiful bush home.

Two more frogs have moved into the shack, bringing the population to five. They've changed colour from a deep, deep green to a lighter olive. Their poops are everywhere but I like them hanging around, so long as the tigersnakes don't come hunting them.

I made a nice, high bed, just in case.

After six days on my own, I was beginning to feel a bit stir crazy out there on my own. Digger was good company but he agreed with everything I said (plus he snores).

I packed up and headed back into town. Old Salt had been trying to ring me for two days.

"Are you in hibernation or something?"

"Been out at Kundip."

"Ah. Same thing. Look, ah, you've got one of my fish bins, haven't you?"

"Yep."

"Well, I'm gonna need it. I got Pallinup."

"Oh. Wow."

Only three estuarine fishers get to work the Beaufort inlet season. Every year they have a ballot. Old Salt was there four years ago. So was I and that was when I started writing about the inlet fishermen and photographing them. We were expecting to work Pallinup next year. Old Salt was going to hang up his boots after that.

"Nails dropped out, so I got it."

I could just hear him waiting for me to ask. He was going to make me ask.

"So. You'll be wanting a deckie, then?"

It seems that whenever I made a hard and fast decision about anything, I get challenged on it - usually immediately. Fickle, dastardly Fate, she says, "Oh you really reckon you can wrangle your life into something vaguely respectable, darlin'? Well try this wild card," and flings it at me, getting me right between the eyes.

I'm already arranging my writing tent in my mind. I can't wait!

Labels:

Buy me a boat,

camping,

disaster puppy,

fisherwoman,

fishing shacks,

inlet,

Kundip,

Mullet,

Old Salt,

on the road again

Homer Said

And if some god should strike me, out on a wine-dark sea, I will endure it, owning a heart within inured to suffering.

Friday, April 13, 2012

Harbour Swim

Stormboy's first open water race was around a few buoys and back. On Easter Saturday he swam the whole harbour; four kilometres from the Boatshed to the yacht club. That's him up the front, head bowed, skateboard scar on his shoulderblade. He's fourteen.

The night before while he was freaking out, I told him that Doust, Haimona and a dozen others would be right with him in canoes. "Someone will be there to reef you out of the water if you get tired. Don't worry if you can't swim the whole way."

"I'm not getting reefed out!" He said.

It was quite a strange experience as a mother, watching him take to the water and swim around the heads of the marina, heading for the open sea. I couldn't walk along the shore and watch him. He just swam straight out to sea.

I drove to our new home which is half way around the harbour, thinking I had another hour before I met my son on the other side. It was about nine and I made myself a leisurely cup of coffee. Mum rang. "He's come in. You'd better get here. He needs you."

"Shit! What time is it? What? How the hell did he get there so fast?"

"An hour and seven minutes," she said.

Stormboy was quite blue when he got out of the water. He said that five hundred metres before the yacht club, the swimmers hit a cold current that felt like a brick wall. His hands hurt and he was shivering uncontrollably. He was wobbly when I got there ten minutes later and he didn't want me to touch him. (I remember the same feeling after finishing the Avon Descent but, being a teenage girl, I was allowed to burst into tears.)

Friday, April 6, 2012

Stories From Policeman's Point

'Show me the place,

help me roll away the stone ... '

On my recent trip to Tasmania I stayed the night with a woman who is descended from the Bass Strait Islanders (in fact she is an islander herself and her husband is a fisherman from those parts). Patsy and Graeme live on the north coast in a village called Tomahawk and she took me for a 'history' drive around the north east coast.

Above is the Ringarooma River, the border of the great chief and warrior Manalargena's country. Rohan Wilson wrote a ripping yarn recently with Manalargena as the main character. You can read my review of his book here. Patsy told me that the Ringarooma used to be a big, deep river; in the tradition of Tasmania and New Zealand's great rivers; but that it has been silted up because of industrial work upstream.

We passed Mt William, where the Pallawah men would light fires to communicate with the Tyreelore, the clanswomen who had been stolen by the sealers to live on the islands of Bass Strait.

.... and several trees that folk used to bury their dead within ...

At Gladstone we stopped to eat a muttonbird pie. This was the height of my Tasmanian experience. Muttonbird pies are full of oily, red meat from the islands, with peas and carrots and a gorgeous crusty pastry to die for. All from a servo in a town out the back of nowhere. When I lived in Tasmania we used to buy the fresh muttonbird carcasses from road side stalls and roast them. One each. We'd carve up a shearwater each on our plates. It was fishy, gamey meat.

Patsy said to me, "They weren't called muttonbirds because they tasted like mutton. Mutton was the name for meat, any meat. Mutton fish was the name for abalone, remember?"

We headed up to Policeman's Point, near Anson's Bay, where there was a historic meeting between George Augustus Robinson and the local tribes. (c1831)

Robinson's job as the 'conciliator' was to bring in the Tasmanian tribes during the Black War, get them out the way of the settlers' and the Van Diemen's Land Company guns, 'pacify' the warrior tribes who were attacking land grabbers and other random whites - and take them to the Promised Land, Flinder's Island, or another island. Any island.

Here is a sobering fact when considering the circumstances of this particular meeting. During the Black War in Tasmania, the ratio of Aboriginal deaths to European deaths was roughly 2:1. On the Australian continent, the ratio of deaths during frontier violence was (a heavily disputed and argued) 20:1. Number crunching is tricky stuff. The argument about numbers when it comes to colonial killings in Australia can be an odious practice. But whatever the way that us contemporary historians explain it, it is obvious that the Pallawah fought hard for about eight years.

Policeman's Point was the place where one of the chiefs (and I think it was Manalargena but I could be wrong) met with Robinson and agreed to help bring in the last of the Pallawah tribes. By then the Pallawah warriors were exhausted with war and they'd seen a huge number of their people struck down by disease, namely the common cold. The Europeans had carried off most of their childbearing women.

Truganina would have been at Policeman's Point that day. Walyer the warrior woman was probably up at Cape Grim causing havoc with her muskets and spears and siblings. I think Peevay and Wooreddy were there, at the meeting.

It was poignant, standing on the point where the inlet rushed out to the sea and hearing Patsy tell the story of that meeting at Policeman's Point. Sea lettuce crawled all over the black basalt. Patsy went looking for penguin shells to string up into necklaces and I fell in love with bull kelp all over again. It was a singular experience to walk where such a history unfolded.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)