A boy with brown feet and brown eyes has been

hanging around me over the last few days. His parents and siblings are camping

nearby. When I first met him he was trailing a thick sisal rope tied around his

waist and was trying to tow the campervan away with his brute strength. Later,

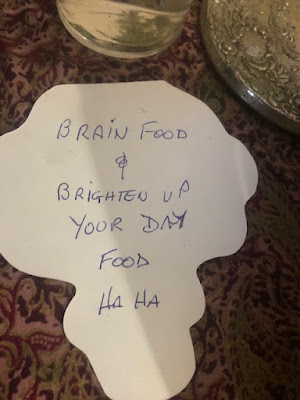

he followed Selkie back to my house. He carried two bamboo sticks that he’d

been carving. We’ve spent hours going through my boxes of big and little

treasures; jewellery, sharks’ teeth, whale bones and gemstones. He announced

that the fossilised megalodon tooth and the smaller of the curved sperm whale teeth

were his favourites.

‘What about Fergal?’ I asked him.

‘Fergal?’

‘Yeah, Fergal Sharkie,’ I said pointing to the

stuffed carpet shark hanging on the wall.

‘Oh, he’s alright,’ he said. ‘But the fox skin

is better.’

I could feel my seven year old alter ego swell

with pride.

On the beach just down from the house are

gemstones, clusters of tiny stones coloured like garnets and amber. The larger

stones contain striations of gold and chocolate, kinda like those chef-endorsed

ice cream brands. When the inlet fills, the corals and other critters colonise

the stones, living all over or under them. Mullet feed on the coral aggregates.

In the 1950s, someone built a break water for the boats. It’s possible they

constructed it from ancient Aboriginal fish traps. Fish trap stones,

concentrated in one place from hard labour a long time ago, are an easy

source of stones.

When the huts were all broken into a few months

ago (read all about the dastardly Quokkas here), a lot of the hut owners came

down to the coast to inspect the damage. Most of them live in far flung inland

towns and having a hut ‘at the coast’ is one of those deliriously wonderful privileges

open only to the generation previous to me. That is, unless you own several CBD

premises, a city beachside house and a business that allows you to call

yourself an interior decorator (ie you sell tiles).

So, I was out the back of Hyacinth and Rupert’s

hut with them, inspecting where the thief had broken a window to get in, when I

looked down to see stacks of Broke Inlet stones from the beach. There weren’t

only a few stones. I was looking at hundreds, if not thousands. Given the

earthworks, I gathered H & R had taken them from the beach to build a

retaining wall. The corals snail-trailed over the stones were calcifying as

they died.

‘Where did you get those stones from, Hyacinth?’

‘Oh, we hauled them here,’ she said, striding

away, ‘from somewhere else.’ Both were stressed about the break in and so I

left her lie where it lay. It was obvious they’d come from the beach. One half

of the wall was already cemented in.

After ruminating on the stones for a few weeks,

I sent Hyacinth a text message. ‘Please put back the Broke Inlet stones. They

are habitat for all kinds of critters and should stay where they are. They’ve

provided homes for invertebrates and fish for tens of thousands of years and

you are using them for a retaining wall? Really?’

Didn’t hear back.

Another month. I bailed up the Parks and

Wildlife ranger outside the Post Office. ‘Here’s a hypothetical for you .. say

someone was building a retaining wall at Broke Inlet, using the stones from the

beach …’ She looked at me warily. ‘Look,’ I said. ‘I’ll get rinsed if I dob

anyone in. It’s the Code of the Coast. What happens at the Coast stays at the

Coast. But I know this is wrong. How do I change their minds about this? Is it

actually illegal?’

It is illegal to remove any natural material

from below the low tide mark, according to the 1984 CALM Act, an Act I’ve

always railed against, but anyway. So, I sent another text to Hyacinth. ‘Would

you like me to save your backs and a criminal conviction? I’ll put the stones

back myself if you like.’

For someone so status oriented (I haven’t

called this character after Hyacinth Bucket for nothing) she sure kept her

cool. She replied that her and Rupert had so many family issues going on right

now, they would deal ‘with the problem as soon as humanly possible.’

While I was glad ‘the problem’ had been

recognised as a problem, I began to entertain doubts about my stand. Yowie

changed the subject whenever I brought it up, as did other squatter hut

dwellers. Maybe they thought I was a crank or a control freak. Maybe I was

wrong? Maybe I was one of those tree changer newcomers who starts up a ‘Friends

of XXX’ group and becomes a total pain in the bureaucratic arse? I asked Flame’s

partner, an old-time resident, what he thought. ‘No, it’s fucked,’ he said. ‘They’ve

got enough money to buy whatever they want. They just felt entitled to take

those stones. It’s fucked.’

‘As soon as humanly possible’ involved Hyacinth

and Rupert cementing the rest of the Broke Inlet stones into the retaining wall

the next time they came down from the city. When I saw the slopped cement over

the corals and the stones, I felt disappointed in them and in myself. All I

wanted was for us all to be better people.

No one at the inlet wanted to talk to me about

it anymore. ‘You’re like a dog with a bone about this,’ said the squatters who’d

agreed with me previously. Outsider folk said, ‘Well I’m glad you are taking up the

fight. I can’t do conflict, myself, so thanks for taking this one on.’ But they had no idea what it is like to live here.

I’d just alienated my only neighbour within 25

kilometres. Hyacinth and Rupert have helped me out in the past but now they

disappeared into their hut as soon as I drove past. The last message I sent to them

was; ‘Hi just letting you know I’ve dismantled part of your retaining wall and

returned the stones to the beach. When you are next down, I’d love to talk

about dismantling the rest of the wall and putting the stones back. Sarah’

I did that on a Sunday afternoon long weekend, in fuck-it mode, in front of

everyone.

I went into Albany after that and learned that

Hyacinth and Rupert would be back that week. Hyacinth slunk into the hut when I

returned (I doubt she will ever speak to me again) and Rupert, once he’d gone

behind the hut to inspect my wilful damage, came out to glare at me. ‘Would you

like to talk tonight about returning those stones?’ I asked him. I was expecting that a good dose of valium would get me through this encounter.

‘There’s nothing to talk about Sarah.’

‘Really?’

‘You took one load back to the beach. We took

another two. We built the retaining wall out of quarry stones in the end.’

‘That is the BEST possible outcome Rupert!’ I

said. No valium required and I kinda half believed his yarn. Big sigh of relief.

And then he offered me some bull herring and I

thanked him.

I have more to say about the taking of stones. It's a biggie in this country and yes, I’ve

done it myself. This is just one story and I’ve had a great few days, hanging

out with a kid who appreciates stones as much as I do.